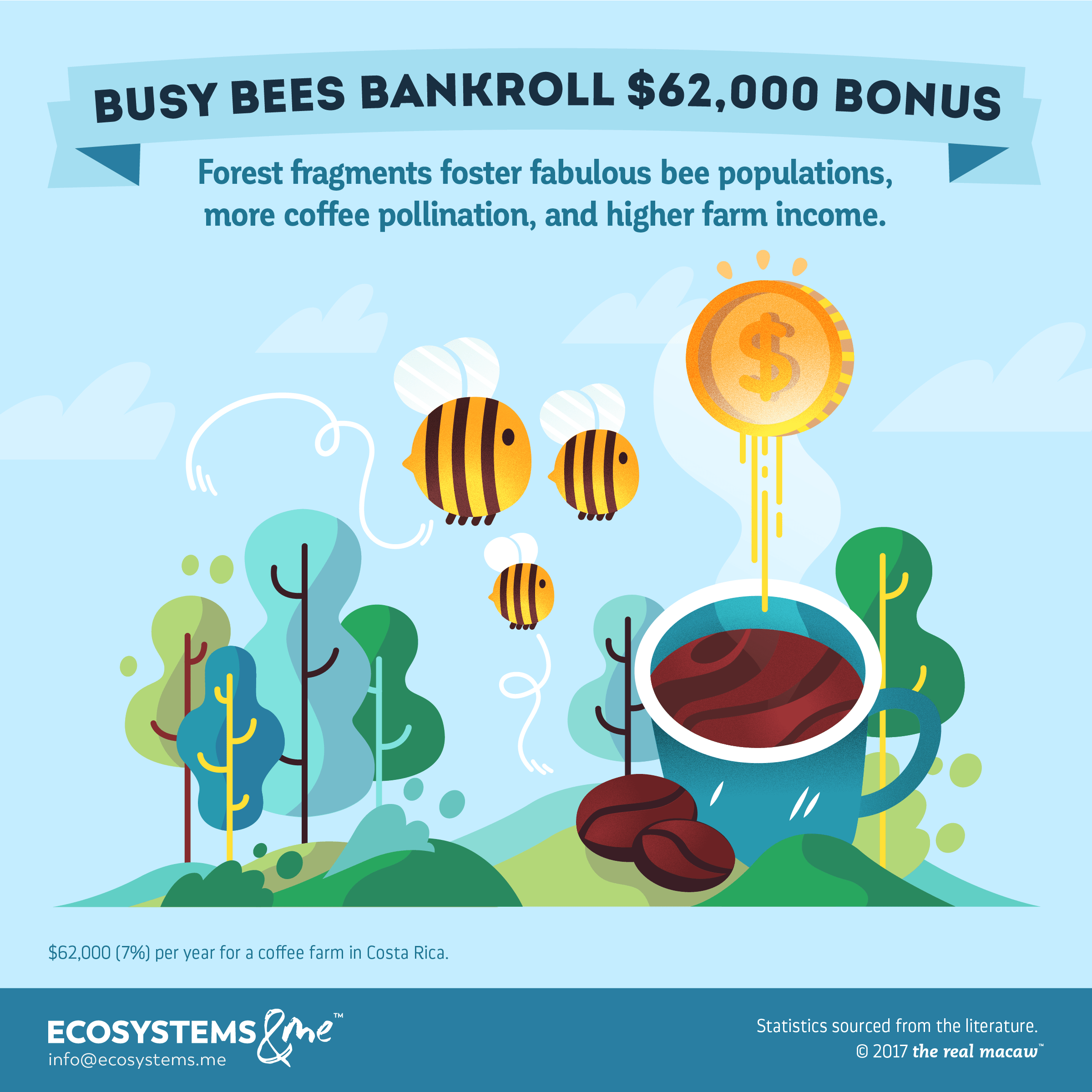

We love coffee. We especially love Costa Rica coffee: it’s considered one of the best in the world. Unsurprisingly, bees love it too… and coffee loves bees right back. Arabica coffee (the only type grown in Costa Rica) can self pollinate (see below), but yields of coffee beans often shoot up when wild bees offer a helping hand. Even more so with a larger variety of bee species, because one bee’s snobbery might be another bee’s treasure. All great news for a coffee farm that happens to have wild bees around – like the one we’re talking about here, which made an extra $62,000 a year just by being near forest fragments that support wild bees. That’s 7% of its yearly income!

But what do bees have to do with coffee beans?

Did you know that coffee beans are actually the seeds of the coffee plant? They grow inside the fruit, which are bright red berries (called coffee cherries) that grow from flowers once they’re pollinated. An Arabica plant can transfer pollen to its own flowers to start the cherries growing, but this isn’t always very efficient, or effective.

Bees make all this better. When they stop on a flower to drink its nectar, they pick up or drop off pollen. This increases the number of flowers that grow cherries, and in many cases, the quality of the cherries too. And that’s how yields increase.

Quality may also improve… from a certain point of view. Usually, you get two beans to a cherry, but sometimes, there’s only one: a peaberry. There’s some debate about whether they’re a delicacy or not, but either way, they generally need extra processing, especially since they often need to be separated from regular coffee beans by hand. So they need to bring in enough of a premium to justify the extra costs of separation, which doesn’t always happen. Well, it turns out that in this case, bees also decrease the amount of peaberries! Sad news for coffee connoisseurs, but probably better for the coffee farm.

Forests and bees

The last piece of this puzzle is forests. Forests provide habitat for wild bees, leading to larger and more diverse bee populations and better pollination.

This happens in two ways. First, bees can only travel so far, so the nearer a farm is to forests, the more bees can visit. And second, a larger variety of bees also means a larger range of bee behaviours. Some bees may make multiple visits to flowers (increasing the chance of successful pollination), while others may deposit more or less pollen, or behave differently during weather or climate fluctuations. The more bees, the more likely their behaviours will complement each other, and the less chance of gaps in their activities. (This, by the way, is why biodiversity supports all ecosystem services.)

As for the forest fragments, it just means that bee populations don’t need a massive area of forest. Which is not to say that large forest areas aren’t valuable; they certainly are, and they provide all sorts of other benefits. But in this landscape, it’s good to know that even small (but not too small!) patches of forest can have a major impact.

The Costa Rica coffee farm

Back to the coffee farm. Sites closer to tropical forest fragments had higher fruit set (number of cherries) and fruit quality (size of cherries, linked to the size and quality of coffee beans) thanks to bee pollination, compared to sites far from the forest – too far for bees to visit. Combining those increased yields with the price of coffee tells you just how much extra profit the forest fragments delivered to the coffee farm: $62,000 (or so) every year. That was 7% of the farm’s yearly income in 2000-2003. And it was all the more important in those years, because coffee prices were low.

The best part is, the farm got all that for free, just because the forest fragments existed. And who wouldn’t want a 7% bonus for free?